By Ed Ting

Updated 5/13/11, 5/17/11, 8/2/11

Meade's 90 mm ETX and Celestron's new C90 - are they giant killers, or pretenders? How would they stack up against the legendary Questar? I had all three scopes at my place for a couple of months in early 2011 and wanted to find out.

Meade 90 ETX: Introduced in 1996, Meade's ETX created a frenzy. It appeared (at least in the ads) that Meade had cloned the Questar for only $495. I remember waiting lists at local dealers (remember when there were local dealers?) Eclipse chasers snapped them up, and people who had always lusted after Questars (this includes me) lined up to buy one. Some of the excitement died down after the scopes started shipping. While the optics were usually very good, the scope was let down by a host of mechanical problems. The drive bases had huge amounts of play, forcing you to place an object at the far end of the field to give the drive time to take up the slack, the focuser and axis locks had a cheap feel, and the 8X21 finder was so inconveniently positioned that it was essentially worthless. Then there was the problem of the secondary baffle's adhesive coming loose over time. This happened to mine, and I watched in horror over the course of a few weeks as the secondary baffle slid down, leaving a gooey residue on the silvered secondary spot. $500 was a lot of money for me back in 1996, and I felt duped.

Meade has gradually improved the ETX over the years, adding the Autostar Goto system (Ah - No more manual adjustments!) refining the feel of the controls, and (finally!) mounting a finder far enough away from the tube to be useful. The price has come down as well, and today you can buy a complete ETX outfit, complete with Autostar and tripod, for the same $500 they were asking in 1996. Those of you who read this site regularly know that I am not exactly a fan of these ETX telescopes. That hasn't stopped me from buying them. The present scope is my third, and it's one of the original "RA" units. As drive fork bases failed over the years, or as owners got sick of dealing with them, many ETX optical tubes have wound up "orphaned" from their mounts. That's how I got mine, which is essentially a spotting scope at this point. The ETX is rumored to be due for a major refreshening.

The 90 mm ETX on a dovetail plate

Celestron C90: Introduced in the late 1970s, the C90 took up the position as the entry level model in Celestron's lineup. Unlike the C5, C8, C11, and C14, the C90 was a Maksutov. It was available in three different versions, and they weren't cheap. My 1980 price list shows the telephoto lens version at $235, the spotting scope at $315, and the fork-mounted astro version at $475. And that's in 1980 dollars, folks. The CPI index from 1980 to 2009 rose about 2.33X, making the astro version the equivalent of roughly $1106 in today's dollars. The scope was saddled with cheap .965" eyepieces, although you could upgrade to a 1.25" visual back (for more money, of course) and a worthless 5X24 finder mounted, like the ETXs, much too close to the tube. Original C90s are much-maligned these days. I've seen used samples on Craigslist for less than $100.

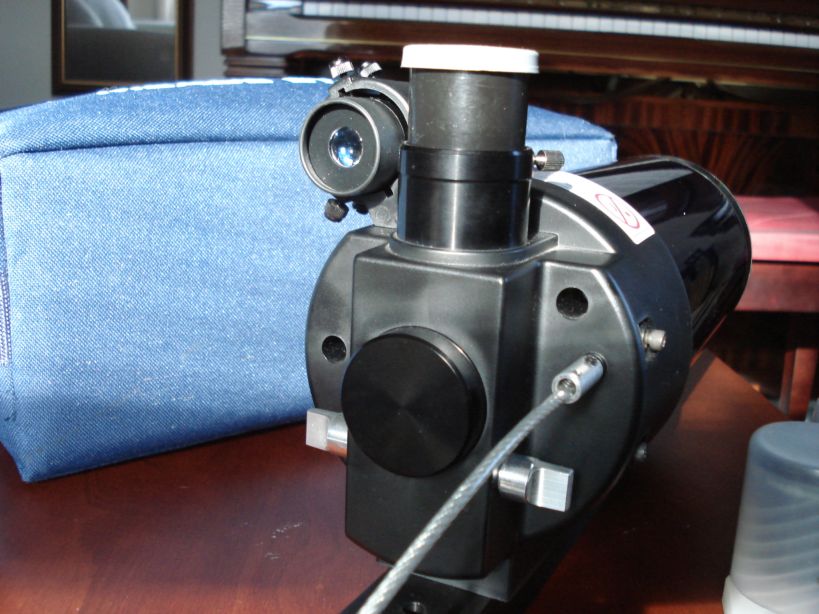

Enter the modern C90. The new Synta-owned Celestron has been making big strides in quality, and they've recently reintroduced the C90. The new scope has nothing in common with the original model; in fact, it looks and feels like a scaled down version of the larger Schmidt-Cassegrains. There don't appear to be any concessions to quality or fit and finish on these entry level scopes. Unlike the ETX, which has large pieces of plastic (most notably in the rear cell) the C90 is made almost entirely of metal. Although not as elegant as the Questar, the industrial-looking C90 has a kind of blunt charm all its own. It feels heavy and serious in your hand. The C90 is an incredible value. You get two eyepieces (32 mm and 12.5 mm) a 45 degree erect image diagonal, and a canvas backpack-style carrying case. It comes mounted on a Vixen-style dovetail plate with little detents for your set screws, a nice touch. Depending on where you buy it, you might also get a (flimsy) tripod with its own case. The best part is the price - less than $200 shipped for all of this from online retailers.

The C90 package - A lot for $200

Questar: Founded in 1950, Questar has been making the same no-compromise telescopes for over 50 years now. The original 3.5" Questar may be the longest continuously-produced telescope in history. They are favored by eclipse chasers and other travelers, by those demanding the utmost in optical and mechanical quality, and by aficionados of fine instruments of all kinds (I've seen Questars displayed in homes as pieces of art.) They are not cheap - models range from $4000 - $6000+ depending on options. If you're thinking of buying a used one, you may be in for a surprise. You will save some money, yes, but not as much as you might think - used Questars, even old ones, hold their value remarkably well, and they tend to be snatched up quickly. If you do wind up looking on the used market, try to get one of the later versions with the DC Powerguide systems.

Questars are quirky telescopes. The 1.25" eyepiece hold has a somewhat unusual mechanical arrangement. Older, models, like the original versions (1950-1968) and early Brandon models (1968-1995) did not support the use of conventional 1.25" eyepieces (we're talking physically, not optically.) Modern Questars, from 1996 on, have an adapter that will allow the use of conventional, and threaded eyepieces like the Brandons (TeleVue also makes an adapter, see below.) The Brandons are admittedly of very high quality, but you may want to use some of your own eyepieces. In most cases, you won't have any problems using "foreign" eyepieces, but from time to time users have reported that some eyepieces won't find focus in finder mode. In general, if you keep it reasonable (no very long or very short focal lengths, no 1.25"/2" hybrids, etc) you won't have any issues. The rear cell has a control to flip between the normal view and a 1.6X barlowed view. In finder mode, you will get 4X or 6X with the standard Brandons.) Thus, with the flip of two levers, one eyepiece can yield three different magnifications. It's all second nature to Questar loyalists, but for me, it took some getting used to.

Adapters to use conventional eyepieces on your Questar - Questar version (L), TeleVue version (R)

Also, the whole tube rotates back and forth in a (roughly) 75 degree arc, allowing you to place the eyepiece at a convenient angle. Finally, who's idea was it to make the focus knob (the most-used control on the whole scope) so tiny? I had trouble finding it in the dark with gloves on. The OTA, with a star atlas embossed on it, is actually a dew shield that slides out. The reveals an inner section with a basic moon map on it. While neither map is especially useful, they give the scope a nice personality. The scope comes with three little tripod legs and an off axis solar filter. My sample is one of the newer versions with the DC Powerguide, which attaches to the bottom of the base using a standard phone connector jack. While I didn't have any problems, I wonder if the cord feeding into the bottom of the base might cause clearance issues with some mounts. The Powerguide is the quietest drive I have ever heard on any telescope. Even when pressing my ear against the scope's housing, I can barely hear the drive running.

My Questar sample was generously loaned to me from the Physics department at Phillips-Exeter Academy in Exeter, NH.

The Questar in its leather case

Mounting the Questar has always been an issue. Like in the ETX, I didn't find the supplied tabletop legs all that useful, but others have reported success with them. You can buy a dedicated tripod, which works well, but it's $1350 and adds a huge amount of bulk to your rig, negating the portability of the scope. And like the ETX, the Questar may not be able to point at southern objects when tilted up on a mount (the tube runs into the base.) For these reasons, the "Duplex" models are now quite popular, as you can remove the optical tube from the fork arms and use your own mount. I wound up using a Tiffen (made by Davis & Sanford) 4800, and a CG-5 for my observing.

Not being a card-carrying Questarphile, I'm not up on all of the lore surrounding the scope. Suffice it to say, there's plenty of it out there. There are all sorts of tales about observers seeing detail, and splitting close doubles far beyond the theoretical limit for a 90 mm telescope. Not blessed with sub arc second seeing at my location, I wasn't able to verify these claims. I can say that this is one gorgeous piece of equipment. The manual slow motion axis knobs are precise and smooth. Pulling the eyepiece out results in a rush of air and a light popping sound. Running your fingers across the rear cell is a pleasure in itself - the word "buttery" was invented to describe how the controls feel.

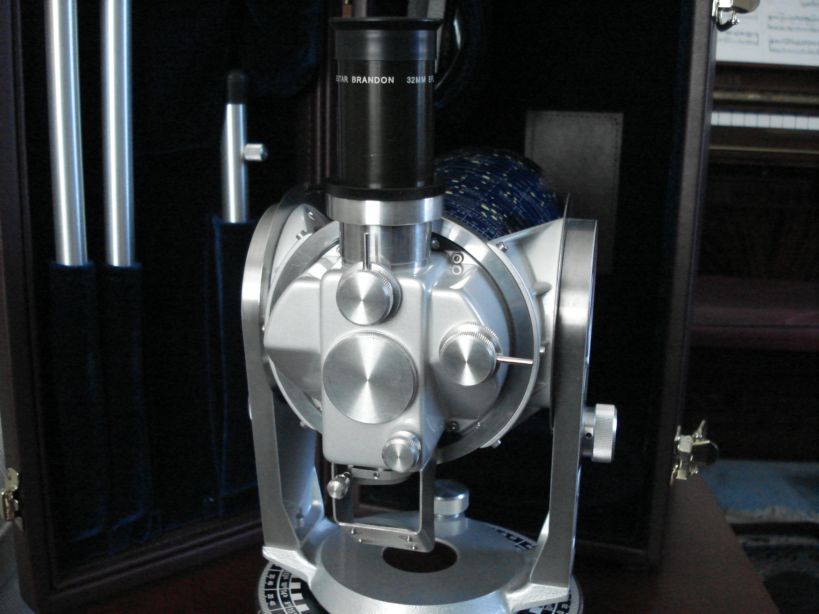

Now, isn't that beautiful?

Observing, ETX vs C90: I used the ETX and the C90 over several nights in February and March of 2011. Both scopes are slightly out of collimation. But neither was badly out, and there's nothing I could do about it in any case. The C90 appeared to have a slightly cleaner star test, but again, the scopes were close optically. Eyepieces used were the TeleVue 32 mm Plossl, the 19 mm Panoptic, the 13 mm Type 6 Nagler, and the generic 32 mm Celestron and MA 25 Meades. I looked at most of the usual suspects in the winter sky: M42, M45, the Double Cluster, M31, Castor, Eta Cass, M35, M37, M36, M38, and M1. Visually, it was hard to tell the difference between the two tubes. I was able to pick out NGC 2158 near M35, and NGC 1907 near M38, for example, in both scopes. Eta Cass showed nice separation with its wine-colored secondary component, and Castor was cleanly split at 96X with the 13 mm Nagler.

So optically, the two inexpensive scopes are a wash. It's in the mechanics that the differences started to show up. And show up they did. For as much as I tried, I could never get comfortable with the ETX. This is my third sample, and every time I buy one I'm reminded of why I sold the last one. The finder is mounted way too close to the OTA, so if you have a head larger than a squirrel's, it's almost impossible to look through it at certain angles. Also, the crosshairs are way too thin and are essentially invisible. The cruel thing is, with a 1250 mm focal length, you really need a good finder. Later versions of the ETX do address this, but there are plenty of older units like mine floating around out there. The focusing knob is tiny, and there's too way much image shift. The usual cheap fix for this problem is to rack the focuser in and out repeatedly to spread out the grease. This I did, over and over again with the scope in my lap one night while watching TV. This cut down on the image shift, but there's still enough of it that you cannot focus on any object at high power - it zips out of the field of view before you can draw a fine focus on it.

The C90 has a conventional eyepiece port that sticks out the back of the OTA so you can use it straight through or with a diagonal. There's a port on the back of the ETX, but you need an adapter ($30) to use it. Otherwise you're stuck with the 90 degree flip mirror which doesn't always return to the same position. The C90 also feels heftier and stronger. While I never had any mechanical problems with the ETX, I found myself treating it a lot more gently. So as a result of this, the C90 is much easier to use, and it's the one I grabbed instinctively when I wanted to use one of them for casual observing.

Observing, Questar: Like a team getting a first round bye, I let the Questar sit for a while I played with the ETX and the C90. I had a feeling that once I started using the Questar, I wouldn't want to use the others. For the most part this was true, but things weren't quite as simple as you might think. Yes, I thought the Questar was better, mechanically and optically, than the others. There was no image shift at all - very impressive. The star test was a little hard to read. Looking at both Procyon and Polaris, I saw little or no spherical aberration, but the optics appear to be very slightly miscollimated. It wasn't as bad as the ETX or the C90, but you could see it. Also, the star test reading changed once the barlow was inserted - it got better(!)

The finder is unusual. Flipping a lever routes the optical path through a small lens, and out the bottom of the tube via a diagonal mirror. In this way, you get low magnification view (about 4X in the case of the 32 mm Brandon) without having to move your head from the eyepiece. This may work well in theory, but in practical use there are some problems. First, this "open" arrangement is subject to dew - in damp conditions, the diagonal mirror dews over almost immediately. Second, since there are no baffles of any kind, the finder picks up all kinds of stray light. At best this results in a brightening of the background sky, but in the worst case (if the scope is pointed anywhere near a streetlight) your finder view will be completely wiped out. Third, the finder on this sample isn't perfectly aligned with the main scope. This problem is made worse by the lack of crosshairs. You can make minor adjustments to the alignment of the finder by turning four (really tiny) cemented screws but as the scope wasn't mine, I didn't feel comfortable breaking the cement seals. And on top of all this, you still have to start things off by sighting along the tube, which is one of my least favorite tasks in observing. So, despite my determination to use all the scopes "as is" I wound up temporarily mounting a Rigel Quik Finder on the Questar and the ETX. In the case of the Questar, this felt a little bit like drawing a moustache on the Mona Lisa, but I just couldn't take it anymore.

Solar observing with the Questar

Once past the inconvenient finder, the Questar is a lot of fun to use. I looked at a lot of the winter objects, including M35, M37, M36, M38, M42, M1, The Pleiades, The Double Cluster, M31, Castor, and Eta Cass. I started swapping out eyepieces and found a pleasant surprise - the TeleVue Plossls are nearly parfocal with the Brandons. The flip barlow is convenient, and you wind up using it a lot, but sometimes it would not seat perfectly. Reengaging it would usually solve the problem.

Although I was able to find all of the common winter and spring Messier objects, I can't say it was a lot of fun. A 90 mm telescope just isn't a great deep sky tool, and if you're the type who like to look at dim stuff, none of the scopes in this comparison are going to make you happy. After a few nights, I learned to keep my 12" Dob around just for a change of pace. Where these scopes excel is on the moon, sun, double stars, and planets. Once I trained the scopes on these objects, they began to come into their element. Under good conditions, it's a lot of fun to look at the moon, for example, and see how many craterlets are visible on the floor of Plato. The crack at the bottom of the Alpine Valley is another challenging target. One issue with both the ETX and the Questar is their relatively short eyepiece barrels. If you're going to use a barlow on their 90 degree eyepiece ports, you need a shorty-style unit to keep from bottoming out on the holder (the C90 doesn't have this problem.)

I split some common late winter doubles, including Castor, Kappa Gemini, Eta Cass, and Algieba (Gamma Leonis.) It says something about my seeing conditions that Algieba, at around 4 arc seconds, was the tightest double I could split in two months of observing. I felt the scope was barely breathing hard, but the conditions weren't such that I could go beyond its theoretical 1.3 arc second limit.

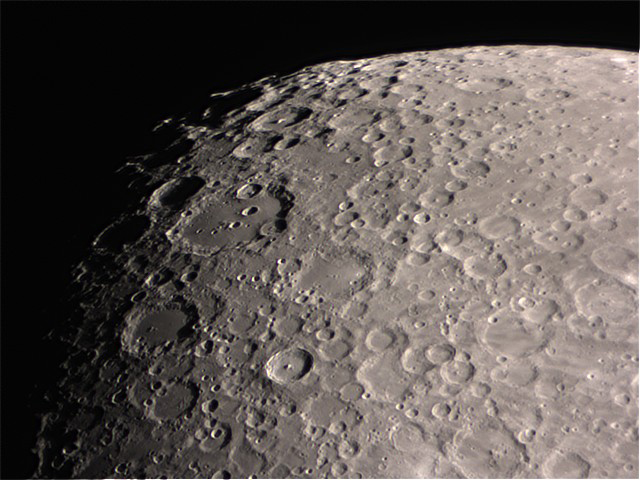

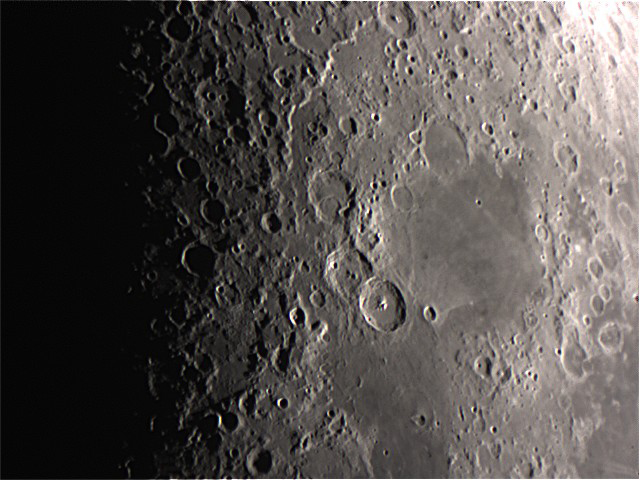

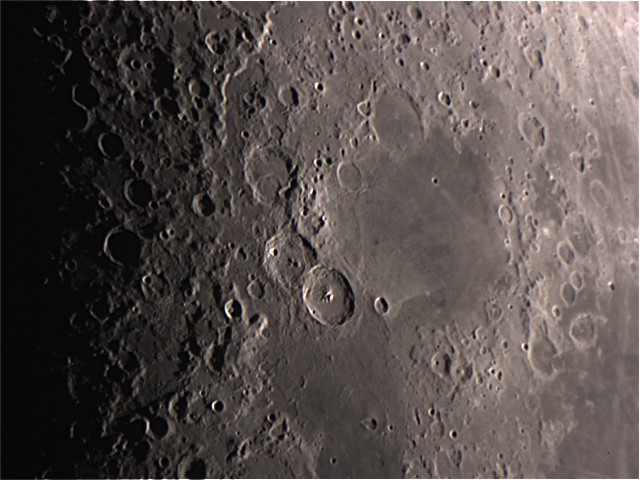

One evening I was able to image the moon all three scopes. Although this is not a scientific test, I did my best to keep the variables constant. The camera was the Imaging Source DBK 21UA04.AS. All images were taken at prime focus using the 90 degree port on the ETX and Questar, and using the straight through the C90. The images were taken within 30 minutes of each other on March 14th, 2011. I left the gain, exposure, and shutter speeds constant. I also processed the images the same way using a saved profile in Registax. The images are the Clavius region, and Plato. The C90's images were flipped N/S and L/R in Photoshop to match the orientation of the others.

Questar: Really, really nice. There's impressive detail and the contrast is just right. The image of Plato is better than the others. It's so good that after seeing this, I was kicking myself for not bumping up the power to see if I could catch the crack in the floor of the Alpine Valley.

C90: Bright. Contrasty. Vivid. Eye-Popping. Over and over again, these traits came through in the C90's images. This was visible visually as well. The C90 had the brightest images by far (new coatings, perhaps?) and could always be relied upon to deliver the biggest "wow factor" of the three scopes. On the other hand "excitement" isn't exactly what you necessarily want with your telescope. I thought the Questar delivered more realistic views. Also, the C90's field isn't quite flat - see the Plato image.

ETX: The ETX gives us something to talk about, but not much. The scope had the dimmest images (this was more obvious during the live capture sessions than the final images would indicate.) Also, for some reason, the ETX yielded a slightly higher magnification than the others (this could also contribute to an overall dimming of the image.) Even taking this into account, the ETX acquitted itself nicely. It's only when you compare detail in Plato and the Alpine Valley to the Questar (above) that you start to see some loss of detail.

The most interesting part of this test is what you can't see on the images above. The Questar was such a pleasure to use. Not only did it provide the best images, it did so with the least amount of effort. I spent the least amount of time focusing the Questar, by far. Although the C90 had no image shift, sometimes I had to rack the focuser back and forth a little to arrive at the best focus. I got good images out of the ETX, but I had to work at it. Also, watching Registax working its way through the images was fascinating. Overall, the Questar yielded more usable frames, per capture, than either of the other scopes. There were times, even with the quality threshold set at at 95% or higher, that close to 100% of the frames were deemed usable by Registax. No other scope I've ever used has come close to that feat.

OK, so far? Good - let's have some fun. I'll show you three sets of images, and you tell me which scope made them. The camera settings were left identical, the captures lasted 15 seconds, and all were processed using the identical wavelet profile in Registax. All the images below were taken within a ten minute time period. I've given you enough clues above that you should be able to figure this out for yourself. I polled the club on this, and most of them were able to get it right. So, let's have a go, shall we? You make the call! (Answers at the bottom of this article.)

Image Set # 1 - C, E, or Q? You make the call !

Image Set # 2 - C, E, or Q? You make the call !!

Image Set # 3 - C, E, or Q? You make the call !!!

Scope photos follow below:

Corrector plate, ETX

Corrector plate, C90

Corrector plate, Questar

Rear cell, ETX (Remote focus cable attached)

Rear cell, C90

Rear cell, Questar - Controls (Clockwise from top) - barlow, finder switch, focus knob, finder port (small knob)

Conclusions:

Optical quality verdict: Questar. Again and again, the Questar's optics beat out those on the C90 and the ETX, both visually and photographically. Sometimes its edge was slight, but most discerning observers could pick out detail in the Questar that wasn't visible in the others. And despite being the oldest scope by far, its 20+ year old coatings have held up.

Mechanical quality verdict: Questar. No contest here. The Q was a pleasure to use. Its controls are silky smooth and the scope invites you to play with it. There's no image shift and images snap into focus in the way that the others don't. While I could get good views and images out of the C90 and the ETX, I had to work a little harder at it. This was especially true in the case of the ETX, which had an annoying amount of image shift, and a cheap plastic feel overall.

Practicality verdict: Questar. The scope just plain works. You can take it with you, its Powerguide works flawlessly and silently, and in a pinch, you can use the three little tripod legs. The ETX clones the concept, but not the execution. Last in this category is the C90, which comes supplied with a useless tripod and needs a full fledged equatorial mount to work properly.

Desirability "Lust Factor" verdict: Questar. Of course. Almost everyone who sees a Questar in the flesh fantasizes, at least for a moment, about buying one. During the review period, visitors to the house immediately made a beeline for the Questar. You can't buy loyalty like that. You already know if you want one. If so, do the right thing. Interestingly, some observers also reported that the little ETX raised their pulses slightly. It's a cute scope with an attractive deep purple finish. Its aluminum dust cap is a high point - it feels like it wandered in from a much higher quality product. Last in this category was the industrial-looking, workmanlike C90.

Value verdict: C90. An embarrassingly good telescope package for almost no money. As of this writing they're practically giving them away. If you've been thinking about getting one of these, I urge you to do so immediately before they run out, or before Celestron stops making them. Just be sure you have a suitable mount for it (ie, not the included tripod.) The C90 is the surprise of the group, offering most of the performance of the Questar at 1/20th of the price. It lacks a driven base, so if you're an eclipse-chaser who must have a portable observatory (and can't afford a Questar) then the ETX might be right for you. Obviously the Questar is last in the value category, but Q owners aren't exactly known as bargain-hunters.

Why have one when you can have six? A harem of Questars at Phillips-Exeter Academy

I spent two months playing with all three scopes and enjoyed my time immensely. I want a Questar, but I can't justify the cost. Maybe you can. Right now, if I had to spend my own money, I would buy a C90. In fact, near the end of the review period, I did just that. (*)

-Ed

(Note: Thanks to John Blackwell, Paul Schroeder, Dan Smith, Larry Lopez, and Neil Rothschild for their contributions to this article.)

(* Note: Two observers, who had following the progress of this review, wound up getting C90s of their own. While one was decent, the other one had fair to poor optics. So there does appear to be some variation on these scopes. Buy new, so that your have some recourse if something is not to your liking.)

(Answers to quiz, above: Set # 1- C90, Set # 2 - Questar, Set # 3, ETX. Image brightness and contrast are big clues. The C90 throws up the brightest, most contrasty images, the ETX the dimmest. The Questar is in the middle - just right. How did you do?)

Sidebar: What fits what on the Questar?

I'm thankful for the various C90 and Questar owners who have helped me clarify certain issues with these scopes. The Questar, in particular, has such a long and rich history that certain variations in the models (not readily apparent to the casual observer) have cropped up. I should stress that if you have a newer Questar it is highly unlikely that you will run into any eyepiece compatibility issues. Even if you have an older Questar, you are probably OK. Eyepiece compatibility should not dissuade you from buying one of these fine scopes.

I got a nice email from Neil Rothschild who writes the following. It's reprinted here, in its brilliant exhaustive detail. Take it away, Neil!

Any

Questar made on or after about 1995 was delivered with the “black collar”

tapped for (and including) two thumbscrews and therefore can accept any 1.25”

eyepiece as well as the Questar-Brandon eyepieces. Your friend likely

bought a new adapter with the thumb screws although he could have had Questar

update his eyepiece adapter as I mentioned previously, tapping it with a couple

of 4-40 threads and adding the thumb screws. For example, my 1985 Q7 and

my 1997 Q3.5 have the identical diopter adapter except for the thumb screws.

The

original Questar has a 0.925” diameter axial adapter in the back of the

control box. Circa 1964 Questar widened the port to 1 3/16” to fully

take advantage of the available light cone. This new axial port is known

as the “wide field version or wide field modification”.

All

Questar diopter adapters, including the original for Japanese eyepieces, have

0.925” threads that match the 0.925” thread at the top of the control box

used with the internal right angle prism. The diopter adapters simply

unscrew from the top of the control box.

Owners

of earlier Q’s with Japanese eyepieces will generally purchase a modern

diopter adapter (with thumb screws) that will take the new

As

you can see, for less than $100 any Questar ever made can be modified to handle

modern 1.25” eyepieces as well as

You

are probably aware that there are two styles of “

Any discussion of the

features and accessories available for a Questar is quite complex. We have

two “user groups” of Questar owners on the web. The oldest group is

located at http://tech.groups.yahoo.com/group/Questar/.

This group has its roots back to a Major-Domo mail list started sometime prior

to 1995. The other group is located in a sub-forum on Cloudynights.com.

Anyone interested in Questars really needs to be a member of one or ideally both

groups.

End 90 mm Mak Comparo